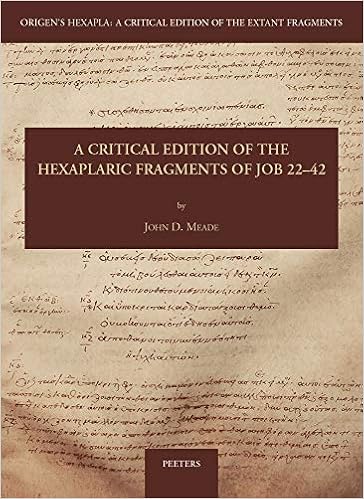

I am very pleased to have had the chance to sit down with my friend Dr. John Meade (at a socially responsible virtual distance of course) to discuss the recent publication of his new book, A Critical Edition of the Hexaplaric Fragments of Job 22-42 (Peeters). John is an associate professor of Old Testament at Phoenix Seminary, where he also serves as co-director with Dr. Peter Gurry of the Text & Canon Institute. (As a side note, the T&CI is up to some fascinating things, such as their recent Sacred Words conference.)

I am very pleased to have had the chance to sit down with my friend Dr. John Meade (at a socially responsible virtual distance of course) to discuss the recent publication of his new book, A Critical Edition of the Hexaplaric Fragments of Job 22-42 (Peeters). John is an associate professor of Old Testament at Phoenix Seminary, where he also serves as co-director with Dr. Peter Gurry of the Text & Canon Institute. (As a side note, the T&CI is up to some fascinating things, such as their recent Sacred Words conference.)

John is well known for his work on the Old Testament canon in general and his publication The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity with Edmon Gallagher. But he is also a part of the Hexapla Institute with Dr. Peter J. Gentry, among others (more on that below). This brings us back around to his most recent work on the hexaplaric fragments of the book of Job, which actually began over ten years ago as his doctoral dissertation. Now, John has already given one interview about this project that is well worth your time as background to this one (read it here), since I’ve done my best not to repeat questions.

You may also want to check out this earlier interview I did with John a few years back. Now onto the new stuff:

The Interview

Congratulations on the completion of this massive project. Can you tell us a little more about the Hexapla Institute and its aims?

Thank you, Will. The Hexapla Institute was established in 2001 due to the vision of Leonard Greenspoon, Gerard Norton, and Alison Salvesen. After Oxford’s Rich Seminar on the Hexapla in 1994 (and the subsequent publication of its papers in 1998) and the IOSCS Congress in 1995, all participants recognized that the time had come to publish a new collection of hexaplaric fragments. In 2001, Bas ter Haar Romeny and Peter Gentry worked to establish the Hexapla Institute, which as of 2002, also operates in cooperation with and under the auspices of IOSCS.

The Hexapla Institute aims to publish “A Field for the 21st Century,” that is, its goal is to make a new critical edition of all remains of Origen’s Hexapla after the vision of Frederick Field, who sought to reconstruct a critical text of all known remains of the Hexapla. Since the publication of Field’s magisterial work in 1875, new evidence for Origen’s Hexapla has come to light, and therefore the need arose for a new critical edition. The Institute seeks to publish these fragments in fascicles through Peeters as well as online in a database, but the latter modality has yet to launch.

Students sometimes ask me “Where is the Hexapla?” because they are thinking about the usual format of critical texts like NA28. Assuming you get the same question, how do you respond?

Well, Will, I’m glad students are asking you where the Hexapla is. To talk about where the Hexapla is now requires a brief explanation of its history. Probably around 235 AD, Origen of Alexandria, the philologist that he was, produced a six-columned edition of the Old Testament scriptures with the following texts: (1) The Hebrew Text (consonantal proto-MT), (2) a Greek transcription of that Hebrew text (included the vocalization), (3) Aquila’s Greek revision, (4) Symmachus’s Greek revision, (5) the Septuagint, and (6) Theodotion’s Greek revision. For some books like Psalms, Origen may have had more Greek editions which he called Quinta and Sexta. Each folio or leaf probably contained 6 columns (three on each side of a gutter) and 40 lines per page with each line containing only one Hebrew word and its Greek equivalents across the page. Someone could have read each column vertically or performed a comparative reading by reading horizontally across the page. Historians, Anthony Grafton and Megan Williams, estimate that the Hexapla would have filled some 40 codices of 400 leaves (800 pages) each (Christianity and the Transformation of the Book, p. 105).

The Hexapla, therefore, was probably not copied in its entirety. Maybe there were later copies made for some books like the Psalter, since there is later manuscript evidence of the synopsis of the Psalter, but this is disputed. But we do know that early Christian scholars traveled to Caesarea to see the Hexapla. It is also probably the case that Origen made another edition which included many readings of the Hexapla in its margins. This edition was probably called the Tetrapla. Therefore, the Hexapla does not exist anymore in toto. We can access the Hexapla only through fragmentary remains found in the margins of Greek, Syriac, and Armenian manuscripts, comments from church fathers (mostly Greek and Latin), and the precious few manuscript remains of the synopsis. The critical edition of the hexaplaric fragments, therefore, includes all known evidence for the readings that were originally in the Hexapla, but since the text of the Hexapla is no longer extant in toto, the critical edition’s text is not continuous like the NA28’s.

What does your critical edition look like and how does it differ in presentation from the typical eclectic text?

Aside from the fact that the text of my edition of Job is not continuous, as I tried to explain above, my critical edition appears as most do. It has a critically reconstructed text of the hexaplaric fragments, sometimes only a word or two, with a series of apparatuses in which appear variant readings to the text. In the tradition of Field, the new critical edition also gives the related Hebrew (BHS) and Old Greek/Septuagint (Joseph Ziegler’s critical edition of Iob) readings to aid understanding the hexaplaric reading. I then supply Notes in the form of a brief commentary on most of these readings.

Besides the book of Job, what books have the most extant Hexaplaric evidence and how do you access those primary sources?

It is true that Job has a lot of evidence for the Hexapla. But there is good evidence for the Hexapla for most of the Old Testament books except Esther, 1-2 Esdras, Chronicles, and Ruth. At this time, the best places to access the remains of the Hexapla are the modern editions of the Septuagint. I have written a post on that over at the Evangelical Textual Criticism blog.

What is the best way for newcomers to get acquainted with the issues involved in Hexapla studies?

There are a few good ways to become more acquainted with the Hexapla. I, and most engaged in this subject, became interested in it via textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible. It’s fascinating to see how Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion rendered the Hebrew text, especially when it might be that they rendered a different Hebrew text than MT. Students of the New Testament might be interested to know that Theodotion pops up in the New Testament in places like 1 Corinthians 15:54’s citation of Isaiah 25:8. By reading the remains of the Hexapla, most become acquainted with it. The book by Grafton and Williams I mentioned above is also a great place to learn more. The Phoenix Seminary Text & Canon Institute has planned a colloquium on Origen as Philologist, which plans to delve deeper into these matters. Unfortunately, most of our introductions to the Septuagint go back only as far as Mercati on the question and have not examined the primary evidence for themselves. Peter Gentry and I are working to provide an accurate account of the history of the Hexapla according to all of the extant source material.

2 comments