Balboa Park, San Diego. Museum of Man pictured right.

One of the things I have been trying to do over the past year and a half or so is to attend and participate in more biblical studies conferences. Some of this I have written about previously (here). It’s a lot of fun, if occasionally overwhelming and often expensive. But it’s also worthwhile. I’m working on a post right now for aspiring doctoral students of biblical studies that will be a kind of “how-to” (and a “why”) for the conference scene, which can be tremendously beneficial to the student. So look for that in a few weeks.

SBL National Conference

The upcoming annual Society of Biblical Literature (SBL) conference will be held from November 22nd-25th in San Diego, CA. The location will be a welcome change compared to the prior two years’ frigid locales, Baltimore and Chicago, respectively. Information about the meeting, including registration, transportation, and housing are on the annual meeting page.

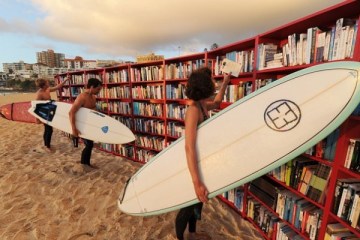

Rumor has it the book exhibit will be on the beach.

I am excited to have the opportunity to participate by presenting a paper this year. I will read it at the IOSCS program unit (here), which usually meets at least twice during the conference. My paper will be an extension of the research I presented at the 2013 IOSOT Congress in Munich, which dealt with Septuagint lexicography in the double-text of LXX-Judges.

In the congress paper I took a brief foray into verifying research done almost fifty years ago now by John A. L. Lee in LXX lexicography. Lee’s work was decisive in demonstrating that LXX Greek is in fact simply the vernacular Koine of its time, not a special “Jewish Greek” that some scholars had posited (for more on the language of LXX, see this post). Lee also dipped into historical linguistics using documentary evidence to establish a terminus ante quem for the translation of the Greek Pentateuch. His dissertation is in print (and quite affordable, here). An abstract of my previous congress paper and its appendix are available here.

My SBL presentation will focus again on LXX lexicography and the Greek texts of Judges. This time I will be considering the translational renderings of the prevalent battle language throughout the book. Words like לחם and מלחמה are translated in interestingly divergent ways in the A text as opposed to the B text. The question I will be asking then is simply, “Hmm… why?” I don’t have a clear answer yet! But I have my suspicions. Lee’s methodology of lexical inquiry in documentary evidence will be a primary avenue of inquiry for this paper (using papyri.info, which I have reviewed in part here). Hopefully come November I will have something cogent to offer in terms of an answer.

A full abstract is available here.

ETS National Conference

I will also participate in the ETS conference, also held in San Diego just prior to SBL, presenting a paper in the Psalms & Hebrew Poetry section. I have not been as active in ETS as I have in SBL in the past few years, so I’m looking forward to being a part of this conference. Although it’s a smaller event by far, it is still a great way to see what is happening academically within the purview of evangelicalism.

I will also participate in the ETS conference, also held in San Diego just prior to SBL, presenting a paper in the Psalms & Hebrew Poetry section. I have not been as active in ETS as I have in SBL in the past few years, so I’m looking forward to being a part of this conference. Although it’s a smaller event by far, it is still a great way to see what is happening academically within the purview of evangelicalism.

My paper is a product of a longer study I did a few years ago in Nahum 1 (here and here). I presented a paper at a regional ETS a year ago that was less extensive (and sparsely attended!), so I’m looking forward to presenting this more in-depth analysis.

The basic issue at hand is the question of the presence (or absence) of an acrostic in chapter 1. Especially in vv. 2-8 there is what appears as a partial, or “broken,” acrostic spanning the first half of the alep-bet. Ever since F. Delitsch mentioned it in his Psalms commentary there have been innumerable attempts to reconstruct it to either a full acrostic (older commentators mostly), or a complete half-acrostic (most current approaches). Although some are content to take the text as is, either as a coincidence or literary device, the majority opinion still leans towards textual emendation, to the extent that even BHS lays out the verses as an acrostic.

My paper considers the warrant for emending the Hebrew text on the basis of a translation analysis of the Greek version, which is ordinarily the primary witness to which those who would emend the text appeal. Without giving too much away, my paper is entitled “There is No Spoon: Text-Critical Question Begging in the ‘Acrostic’ of Nahum 1 .” An abstract is available here.

This allows you to include, alternate, or exclude certain words.

This allows you to include, alternate, or exclude certain words.

Greek fans are sure to love this. Coming this October is An Interpretive Lexicon of New Testament Greek by G. K. Beale with William A. Ross and Daniel J. Brendsel.

“This revolutionary new aid for students of New Testament Greek functions both as a lexicon and as an interpretive handbook. It lists the vast majority of Greek prepositions, adverbs, particles, relative pronouns, conjunctions, and other connecting words that are notorious for being some of the most difficult words to translate. For each word included, page references are given for several major lexical resources where the user can quickly go to examine the nuances and parameters of the word for translation options, saving the translator considerable time.”

“This lexicon adds an interpretive element for each word by categorizing its semantic range into defined logical relationships. This interpretive feature of the book is tremendously helpful for the exegetical process, allowing for the translator to closely follow the logical flow of the text with greater efficiency. An Interpretive Lexicon of New Testament Greek is thus a remarkable resource for student, pastor, and scholar alike.”

An Interpretive Lexicon of New Testament Greek is from Zondervan. It will be a paperback with 96 pages and sell for $15.99.

Greek fans are sure to love this. Coming this October is An Interpretive Lexicon of New Testament Greek by G. K. Beale with William A. Ross and Daniel J. Brendsel.

“This revolutionary new aid for students of New Testament Greek functions both as a lexicon and as an interpretive handbook. It lists the vast majority of Greek prepositions, adverbs, particles, relative pronouns, conjunctions, and other connecting words that are notorious for being some of the most difficult words to translate. For each word included, page references are given for several major lexical resources where the user can quickly go to examine the nuances and parameters of the word for translation options, saving the translator considerable time.”

“This lexicon adds an interpretive element for each word by categorizing its semantic range into defined logical relationships. This interpretive feature of the book is tremendously helpful for the exegetical process, allowing for the translator to closely follow the logical flow of the text with greater efficiency. An Interpretive Lexicon of New Testament Greek is thus a remarkable resource for student, pastor, and scholar alike.”

An Interpretive Lexicon of New Testament Greek is from Zondervan. It will be a paperback with 96 pages and sell for $15.99.